© 2011 All Rights Reserved. Do not distribute or repurpose this work without written permission from the copyright holder(s).

Printed from https://danginteresting.com/who-wants-to-be-a-thousandaire/

On the 19th of May 1984, at CBS Television City in Hollywood, a curious air of tension hung over the studio during the taping of the popular game show Press Your Luck. Ordinarily a live studio audience could be counted upon to holler and slap their hands together, but something was keeping them unusually subdued. The object of the audience’s awe was sitting at the center podium on the stage, looking rather unremarkable in his thrift-store shirt and slicked-back graying hair. His name was Michael Larson.

“You’re going to go again?” asked the show’s host Peter Tomarken as Larson gesticulated. Gasps and murmurs punctuated the audience’s cautious applause, and the contestants sitting on either side of Larson clapped in stunned silence. “Michael’s going again,” Tomarken announced incredulously. “We’ve never had anything like this before.”

The scoreboard on Larson’s podium read “$90,351,” an amount unheard of in the history of Press Your Luck. In fact, this total was far greater than any person had ever earned in one sitting on any television game show. With each spin on the randomized “Big Board” Larson took a one-in-six chance of hitting a “Whammy” space that would strip him of all his spoils, yet for 36 consecutive spins he had somehow missed the whammies, stretched the show beyond its 30-minute format, and accumulated extraordinary winnings. Such a streak was astronomically unlikely, but Larson was not yet ready to stop. He was convinced that he knew exactly what he was doing.

Michael Larson was born in the small town of Lebanon, Ohio in 1949. Although he was generally regarded as creative and intelligent, he had an inexplicable preference for shady enterprises over gainful employment. One of his earliest exploits was in middle school, where he smuggled candy bars into class and profitably peddled them on the sly. This innocuous operation was just the first in a decreasingly scrupulous series of ventures. One of his later schemes involved opening a checking account with a bank that was offering a promotional $500 to each new customer; he would withdraw the cash at the earliest opportunity, close the account, then repeat the process over and over under assumed names.

On another occasion he created a fake business under a family member’s name, hired himself as an employee, then laid himself off to collect unemployment wages.

By 1983 Michael Larson had been married and divorced twice and was living with his girlfriend Teresa Dinwitty. During the summers he operated a Mister Softee ice cream truck, and during the off-season he passed the time poring through piles of periodicals in search of money-making schemes. Michael also spent much of the day with his console television, scanning the airwaves for lucrative opportunities. One day it occurred to him that he could double his information intake by setting a second console TV to beside the first and tuning it to a different channel. Soon he procured a third. Eventually he added a row of smaller televisions atop the three consoles, and yet another row of tubes was later stacked atop that. Now he could watch 12 channels at once.

The warm, buzzing television tumor metastasized into adjacent rooms, filling the house with a goulash of infomercials, news programs, game shows, and advertisements for money-making schemes. Larson watched them in a trance-like state, sometimes throughout the night. Dinwitty would later say of her boyfriend and common-law husband, “He always thought he was smarter than everybody else,” and that he had a “constant yearning for knowledge.” But when visitors asked about the chattering mass of receivers she found it easier to just tell them that Michael was crazy.

One fateful November day in 1983, Peter Tomarken’s dapper countenance appeared on one of Michael’s many monitors. Tomarken was the host of a new game show called Press Your Luck which was giving away more money than any other game shows at the time. What most interested Michael was the game’s “Big Board,” an electronic array of prize boxes which operated by lighting up squares in a rapid and random fashion until the player pressed a big red button to stop the action. The player’s randomly selected box might contain a vacation, a prize, cash rewards, and/or extra spins. But with each spin there was also a one-in-six chance of hitting a Whammy which would cause an animated character to appear on the screen and expunge all of a player’s winnings.

Larson invested in a newfangled video cassette recorder and began taping episodes of Press Your Luck. After weeks of painstaking scrutiny Michael realized that the bouncing prize selector did not actually move randomly; it always followed one of five lengthy sequences. This information was only moderately useful due to the rapidly shuffling positions of the prizes and penalties, but his methodical analysis led to another finding. Of the eighteen squares on the Big Board there were two that never had Whammies: #4 and #8. This meant that all a player must do to avoid Whammies—and thus retain his hundreds of dollars in winnings—would be to memorize five interminable series of numbers and develop superhuman reflexes. Giddy with the thrill of discovery, Larson began fine-tuning his timing using his VCR’s pause key as a surrogate big red button.

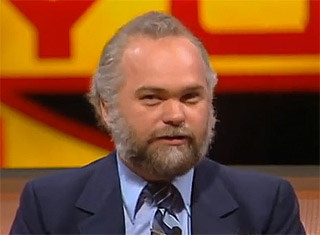

Six months later, in May 1984, Michael Larson sat beardily in the interview room for the Press Your Luck auditions in Hollywood. His story left few heartstrings unpulled: He explained that he was an unemployed ice cream truck driver. He had borrowed the bus money to get to Hollywood from Ohio because he loved Press Your Luck. He had stopped at a thrift store down the street to buy a 65 cent dress shirt. And he was unable to afford a gift for his six-year-old daughter’s upcoming birthday. Executive producer Bill Carruthers said of Larson’s audition, “He really impressed us. He had charisma.” Contestant coordinator Bob Edwards was uneasy about Larson, but he couldn’t quite articulate why, so Bill overruled him. “I should have listened to Bob,” Carruthers later chuckled.

Taping occurred the following Saturday. Returning champion Ed Long sat on Michael’s right and contestant Janie Litras sat on his left. Host Peter Tomarken made boilerplate game-showey chit-chat with each contestant, and he asked Michael about his ice cream truck. “You’ve kind of OD’d on ice cream, right?” he asked Larson, who agreed. “Well hopefully you won’t OD on money, Michael.”

Michael earned 3 spins on the Big Board in the first question round, giving him 3 opportunities to test the skills he had cultivated over the past six months. The board’s incandescent selector began its distinctive pseudo-random maneuvers. “Come on…big bucks,” Michael chanted, as was customary for players when up against the Big Board. “STOP!” he shouted as he slapped the button with both hands. The selector was stopped on a Whammy in slot #17. Michael shook his head and forced an embarrassed smile, but now he knew exactly how the board was timed with respect to the button. With his second and third spins Michael found his stride. He dropped all pretenses and remained silent as he concentrated on the light bouncing around the big board. Both times he successfully landed on space #4, and he ended the first half of the game with $2,500.

In the second and more lucrative half of the game, Michael managed to acquire seven spins to use on the big board. Since he was in last place he was the first to spin. He positioned his hands over the button with interlocked fingers and impatiently interrupted the host’s banter by shouting, “I’m ready, I’m ready!” Tomarken indulged him, and the light on the big board began bouncing. Again, Larson was silent as he frowned at the board. Fellow contestant Ed Long would later say of Larson during these moments that “he went into a trance.”

Thus began Larson’s inconceivable procession of winning spins. His demeanor alternated between intense concentration and jubilation. The strategy worked even better than he had anticipated due to the large number of Free Spin bonuses that appeared in his safe slots. Host Peter Tomarken became increasingly flabbergasted each time Larson made the “spin again” gesture. $30,000 was considered an extraordinary payoff for one day on any game show at that time, and the likelihood of missing the whammies for more than a dozen spins was considered to be vanishingly small. By his 13th spin Michael had $32,351 and nervous giggles. By his 21st spin he had $47,601 and conspicuous anxiety. But he pressed on.

The Press Your Luck control booth had grown silent as the show’s producers began to realize that Larson was consistently winning on the same two spaces. In a panic, the booth operators called Michael Brockman, CBS’s head of daytime programming. “Something was very wrong,” Brockman said in a TV Guide interview. “Here was this guy from nowhere, and he was hitting the bonus box every time. It was bedlam, I can tell you.” Producers asked if they should stop the show, but Larson did not appear to be breaking any rules so they were forced to allow the episode to play out.

Back on the stage, Ed and Janie clapped incredulously on either side of Michael, still waiting for their turns on the board. Janie let slip a snort of disgust after Michael’s 26th successful spin. Tomarken covered his face with his hand in disbelief as Larson risked almost $75k on his 32nd spin. But Michael’s zen-like concentration was beginning to falter. He paused to set his head on the podium and let out a whimper of exhaustion. Still he motioned to continue. The studio audience worried that he’d hit a whammy and experience an unfortunate reversal of fortune, while the producers in the control booth worried that he wouldn’t.

On his 40th spin Larson’s scoreboard debt-clocked his dollar sign to make room for another digit; he surpassed $100,000. Larson, his shoulders slumped, passed his remaining spins to the bewildered Ed Long. Ed immediately hit a whammy.

Michael sat in a twitchy daze as Ed and Janie went through their much more pedestrian turns at the board. But Larson was snapped back to reality when Janie passed 3 of her spins to him. According to the game rules he was obligated to use them. He did not appear pleased.

“I didn’t want them,” Larson joked nervously as the light began bouncing around the big board, yet almost immediately he punched the big red button and landed on $4,000 in slot #4. Janie let out a squeal. The board started again. After a longer than usual delay, Larson hit the button again, landing safely in slot #8. He had just one mandatory spin remaining. The board started flashing, and Larson let out a sigh. “STOP!” he shouted as he slapped the button, but he had pressed it a fraction of a second too soon. Slot #17 was lit, the same slot where he’d hit a whammy on his first spin. As luck would have it, however, the slot contained a trip to the Bahamas. It was over; Michael had won. Larson gave Ed an awkward embrace and offered Janie a firm handshake. In total, Larson won $110,237 in cash and prizes, including two tropical vacations and a sailboat. Reportedly this was more than triple the previous record for winnings in a single episode of a game show.

A clearly discombobulated Peter Tomarken engaged Larson in an impromptu interview after the show. “Why did you keep going?” he asked.

“Well, two things:” Michael replied. “One, it felt right. And second, I still had seven spins and if I passed them, somebody could have done what I did.”

Tomarken was too polite to remark on the ridiculousness of that suggestion. “What are you going to do with the money, Michael?”

“Invest in houses.”

Larson was not allowed to return as champion since he had surpassed CBS’s $25k winnings limit. As all of the perplexed parties parted ways, CBS executives were called to a meeting to dissect the episode frame-by-frame. In spite of their efforts they could find no evidence of wrongdoing or rule-breaking, so after a few weeks they grudgingly mailed Larson his check. Some people at CBS didn’t want the over-extended episode to be released to the public at all, but it was ultimately decided to air it in June as an awkwardly edited two-parter.

Executives insisted that the episode never be seen again. In the meantime Press Your Luck paid to add some more sequences to the Big Board to prevent future contestants from mimicking Michael’s strategy.

Upon his return home, neighbors were shocked to learn of “crazy” Michael Larson’s accomplishment. True to his word, he regaled his daughter with expensive birthday gifts and invested some of his spoils in real estate. But his fondness for dicey get-rich-quick deals ensnared him in a Ponzi scheme, and he lost enough money to lose his appetite for houses.

Some months later Michael Larson saw another opportunity to stack the odds in his favor with a dash of ingenuity. He walked into his bank one day and asked to withdraw his entire account balance, but with an unusual stipulation: He wanted as much of the cash as possible in one dollar notes. The bank complied with his unorthodox request, and from there he proceeded to another bank to trade even more of his savings for singles. Over a two week period he converted the $100,000 or so that remained of his personal savings into 100,000 one dollar bills.

The motivation for this aberrant behavior was a contest put on by a local radio station. Each day a disk jockey would read a serial number aloud on the air, and if any listener was able to produce the matching dollar bill they would win $30,000. Michael reasoned that 100,000 one dollar bills was 100,000 opportunities to win the prize, giving him a statistical advantage. And even if his scheme proved fruitless he would just redeposit his money, so he figured he had nothing to lose.

Michael and Teresa spent each day rifling through piles of cash looking for matches, pausing only for such distractions as eating, bathing, and excreting. They soon realized that it was impossible for two people to examine that much money in the allotted time, so Michael redeposited a portion of it. After a few weeks, Michael’s obsession over the contest began to put considerable strain on his relationship with Teresa, and on his relationship with reality. The cash was stashed in kitchen drawers, up the stairs, and on bedroom floors. They kept the bills in burlap sacks, grocery bags, and unkempt stacks. And though his girlfriend would scream and shout, he simply would not take the cash bags out.

One evening, seeking refuge from the endless hours of cash-collating, Michael and Teresa accepted an invitation to attend a Christmas party. When they returned home at about 1:00 am, they found the back door of the house had been brutalized. Apparently the pair had unwittingly left a sizable tip for an unsolicited cleaning service: about $50,000. According to Dinwitty, Michael immediately accused her of being an accessory to the heist. She denied involvement, and police found no evidence of her guilt, but she says that Larson was never convinced. She claimed that Michael would stand and stare at her while she slept, which made her fear for her safety. One day while Michael was away she took $5,000 that he had hidden in a dresser drawer and absconded with the kids. She called him from a hotel to tell him to move out of her house. His only response was, “I want my money back.” He packed his belongings and departed, leaving one wall of the living room blemished and peeling from the heat of his once-formidable tower of televisions.

Police never identified the thieves. In 1994, about 10 years after his pivotal Press Your Luck appearance, Larson was invited to be a guest on ABC’s Good Morning America to discuss the movie Quiz Show. With a raspy voice he unbeardily reminisced about his game show exploits and expressed regret that he was never able to play on Jeopardy, because, he explained, “I think I have figured out some angles on that.” Around that same time he was also interviewed by TV Guide magazine. When asked about the whereabouts of his Press Your Luck winnings, he replied, “It didn’t work out. We had a cash-flow problem, and I lost everything.”

In March of the following year, Michael fled from Ohio with agents from the SEC, IRS, and FBI hot on his heels. He was implicated as one of the architects of a cash-flow solution that operated under the name Pleasure Time Incorporated. It was a pyramid scam selling shares in a fraudulent “American Indian Lottery” which had hoodwinked 20,000 investors out of 3 million dollars. The Pleasure Time flimflam was historic in that it was the first time the SEC pursued a case where the bulk of the fraud took place in newfangled “cyberspace.” Michael Larson was a fugitive from justice for four years until 1999, when he turned up in Apopka, Florida. He had succumbed to throat cancer.

Michael Larson held the record for the most game-show winnings in a single day until 2006, when it was broken by Vickyann Chrobak-Sadowski on The Price is Right. Larson’s handiwork on Press Your Luck was sufficiently extraordinary that he has become a strange kind of folk hero to some. Others regard him as a cheap huckster or a likable-but-occasionally-creepy crackpot. The real Michael Larson was arguably an amalgam of these qualities. His shenanigans on Press Your Luck are oft described as a “scam,” “scandal,” or a “cheat,” but even the CBS executives ultimately admitted that he had broken nary a rule. In the end, his impressive performance on Press Your Luck may be one of the only honest days of work that Michael Larson ever did.

© 2011 All Rights Reserved. Do not distribute or repurpose this work without written permission from the copyright holder(s).

Printed from https://danginteresting.com/who-wants-to-be-a-thousandaire/

Since you enjoyed our work enough to print it out, and read it clear to the end, would you consider donating a few dollars at https://danginteresting.com/donate ?